If you have a large and scary Monolith and are looking for a clear path of migration to modern Microservices, this post is exactly about that. We are going to take a Monolithic application and, together, step by step, walk through the migration process. Importantly, our application is going to be live in production at all times while we execute our plan. Without further delay, let’s get started!

Table of Contents

The First thing

Before we plan migration, we need to answer a simple question: why? Why do we need to migrate?

- Why do we need to migrate?

- What goals and business objectives are we going to achieve with migration?

- How can our business benefit?

In general, Microservice architecture has multiple advantages compared to Monolith: faster feature delivery (shorter time to production), maintainability (smaller, independent chunks of code are easier to work with), testability (it’s easier to automate testing for a small, independent code base), resiliency (if a single microservice has a bug, the system as a whole may still survive), and so on. If this is what you need to achieve your goals and business objectives, great!

Microservice architecture does not come for free though. It takes a toll in many ways and for many things. For example, it is uncertain how to reuse code and to what extent. Should we copy-paste or create shared libraries? With Monolith, it is rather simple, as there is one code-base where everything is shared. Microservices require certain infrastructure in place; for example, a service discovery mechanism is a must. There might be hundreds or thousands of Microservices that somehow need to communicate. How do we know where to find the one we need, for example, to get a customer’s name by ID?

With Monolith, it’s as simple as calling a known function. Migration to Microservice architecture will require teams and even organisations as a whole to change, adopting new techniques and practices. Handling thousands of independently deployable Microservices cannot be done with the same tools and processes that are used to handle a Monolith. Now we think about CI/CD and DevOps. If the benefits of Microservice architecture outweigh the challenges that come with it for you, we are ready to get started!

Know what you have

Before we take out a “sharp knife” and start cutting the Monolith, we need to identify components that will clearly show us where we may or may not cut. By component, we mean a logically cohesive block of code that is responsible for implementing a single business domain concept. We may have physical modules (namespaces, libraries, packages, etc.) that do not correspond to logical components. If so, the migration process may be harder as we need to refactor physical modules in a way that they are aligned with logical components. For example, we have a three-tier application with Presentation, Application, and Data layers. A single logical component can be scattered across all three layers or modules. We need to bring business logic together into a single component that corresponds to the business domain concept. It is recommended to keep User Interface as a separate layer but extract business logic and place it into a corresponding component.

Flatten and refactor logical components

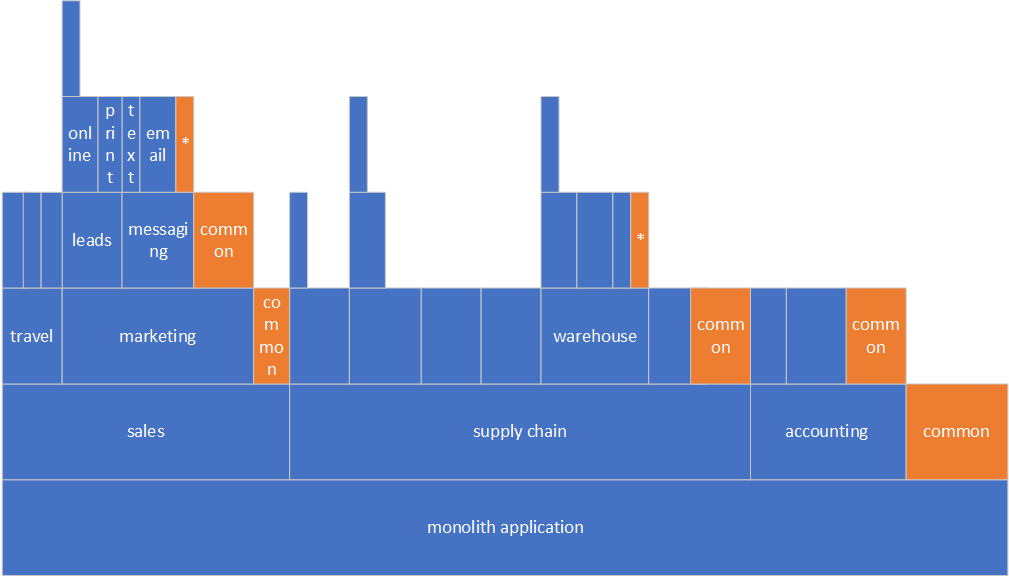

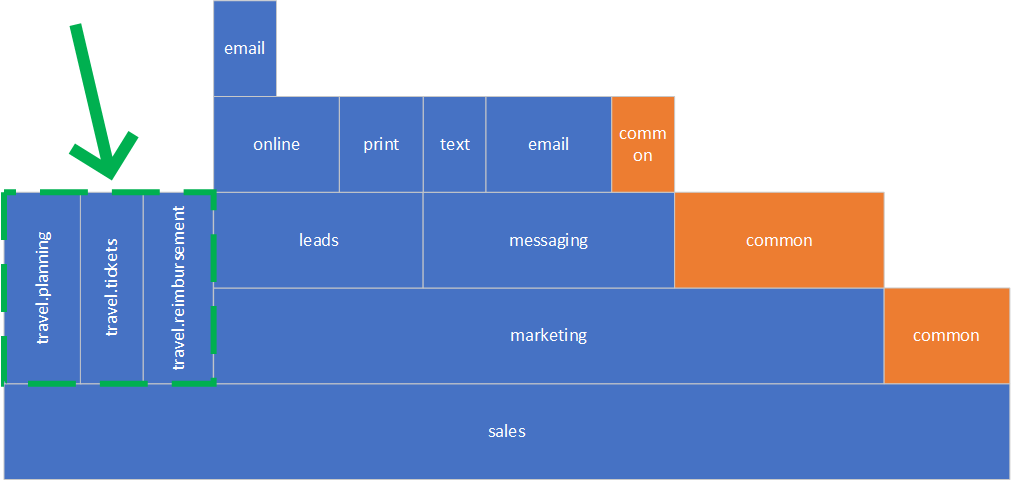

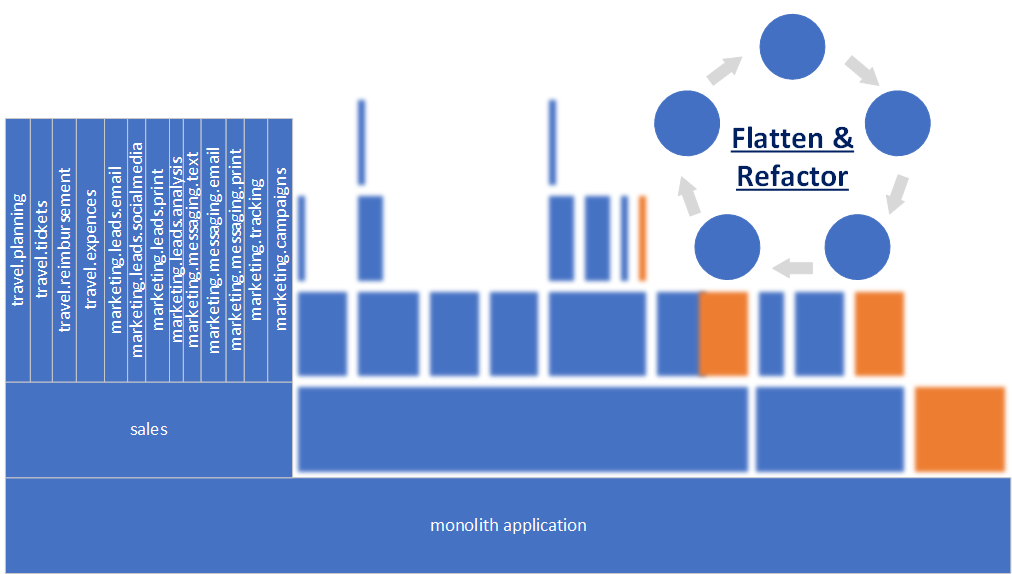

It’s quite difficult to figure out a way to split a Monolith with a tall component’s structure that looks like the Manhattan skyline. Here is an example of such a Monolith. The taller a “building” is, the more deeply components are nested.

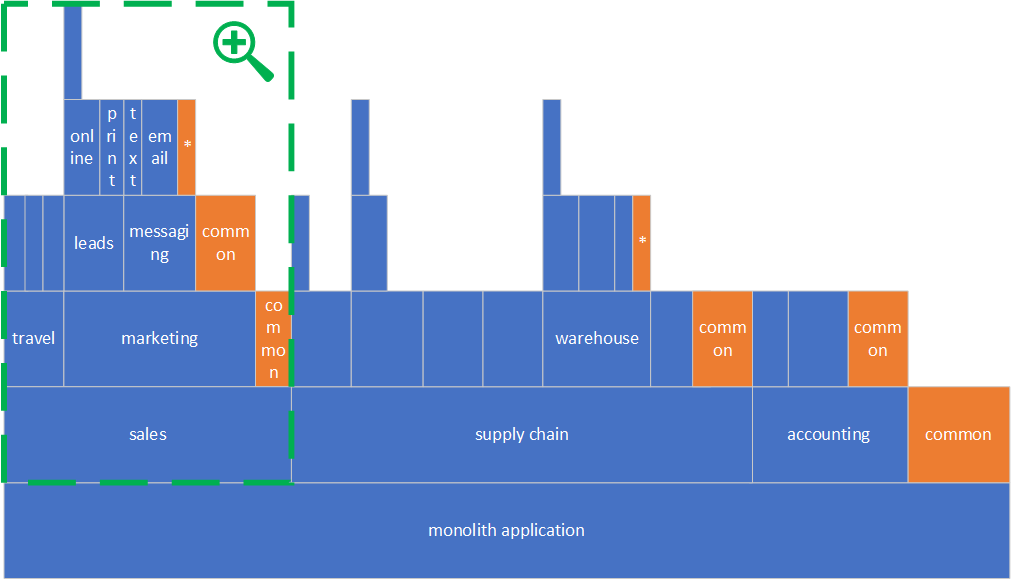

How do we even approach it? Well, we can start working from the top down and flatten the tops of the “skyscrapers”. For the sake of simplicity, let’s just focus on the sales component.

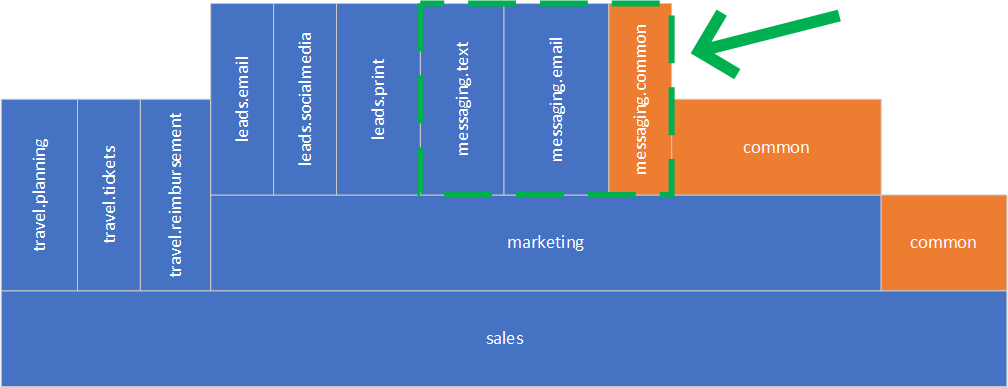

Below is how it looks after we zoomed in. We have two immediate sub-components: travel and marketing, with their own sub-components. There is also common code , orange-colored boxes, that are shared among the travel and marketing sub-components.

Let’s start with travel component first, it seems to be the simplest to tackle as it’s already pretty flat and does not have any shared code among the sub-components.

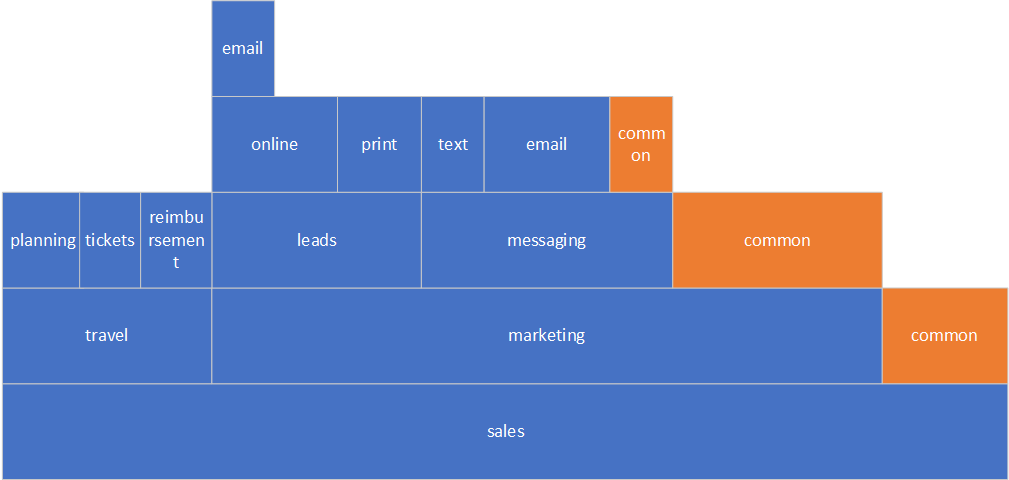

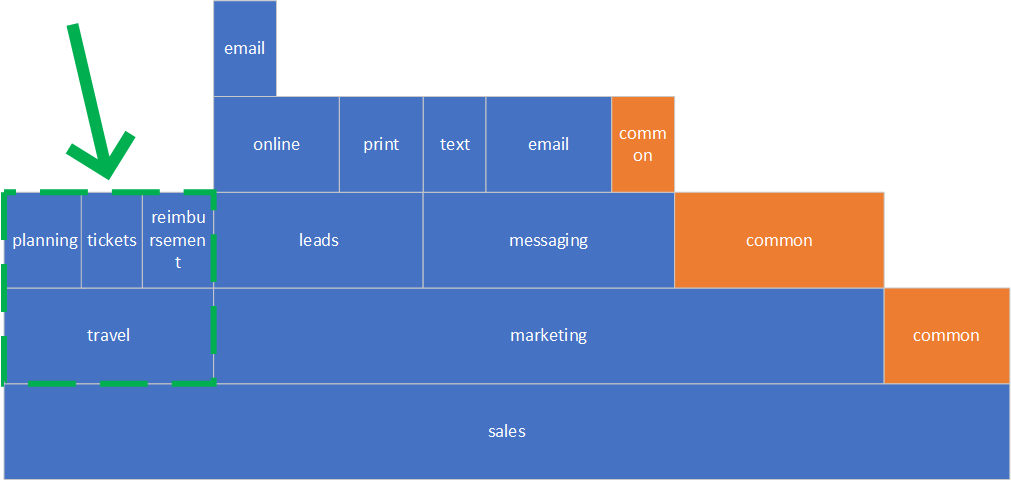

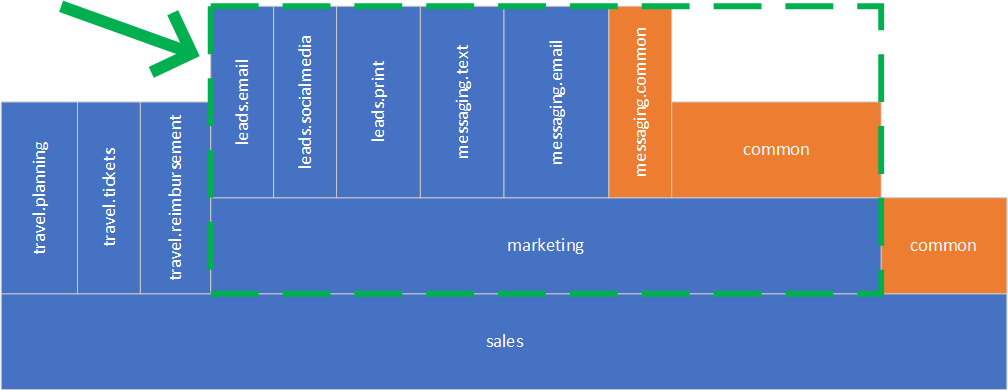

We can simply flatten travel sub-components into a flat structure defining travel.planning, travel.tickets, and travel.reimbursements components. We do not need the travel component itself, because it is just a container and does not have any code of its own. This is what we have now.

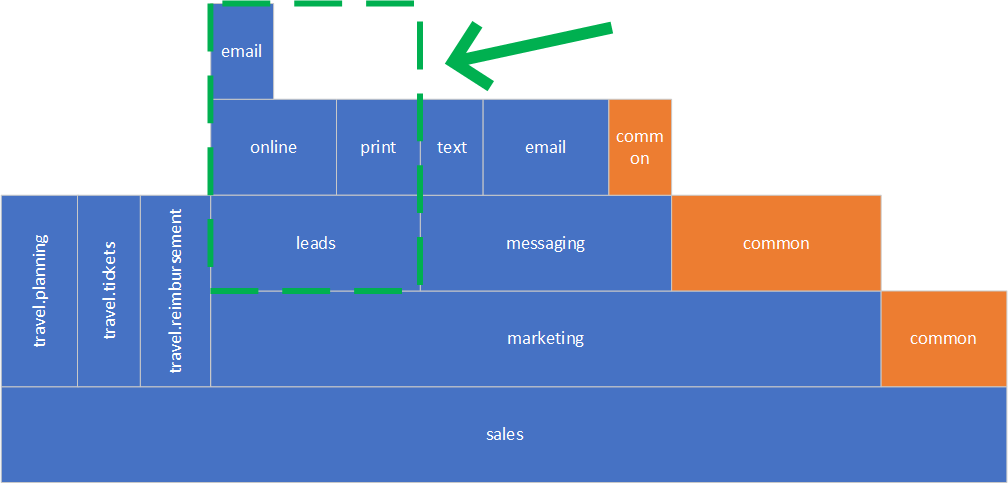

Let’s continue and do the same thing with the leads component. This is more complicated because the sub-components are nested deeper than with the travel component.

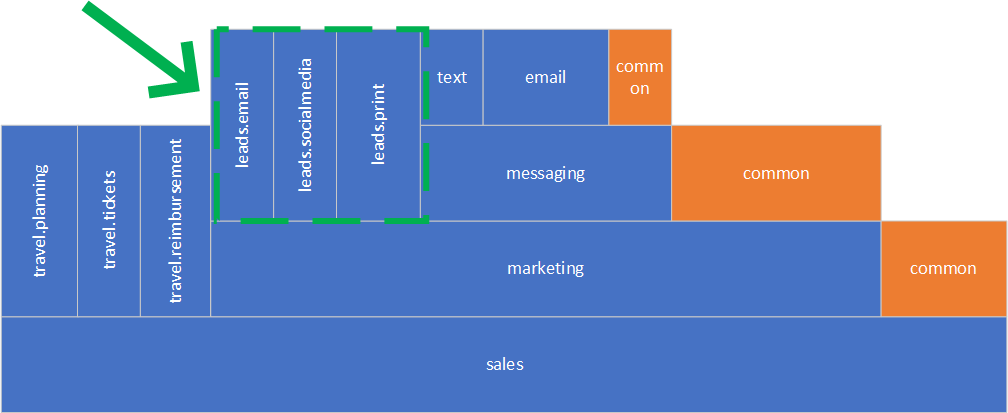

Good for us, we can extract leads.print component right away. Now what do we do with the rest? It very much depends on leads.online code. One possibility is to factor out leads.email into an independent component and then deal with the rest of leads.online code. In our example, we could factor it out into leads.socialmedia as the code was all about social-media leads. This is how our structure looks now.

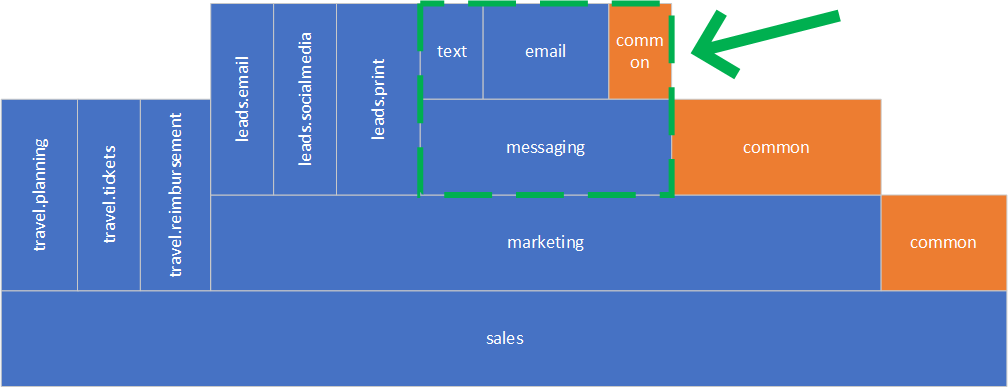

Let’s move to the next component. This time we have common (shared) code among multiple sub-components.

We can factor out messaging.text and messaging.email components using the same approach as above. What do we do with the common code? Let’s look closer to see if we can reduce the need for shared code, move it to appropriate modules, or it might turn out that shared code implements a domain concept on its own, and we can create a meaningful component out of it. However, let’s assume the worst-case scenario, when we still have some common code left and we can’t find a home for it in any other component. At this point, we can just create a messaging.common like shown below.

Looks much better now, but we are not done yet. We still need to deal with the marketing component.

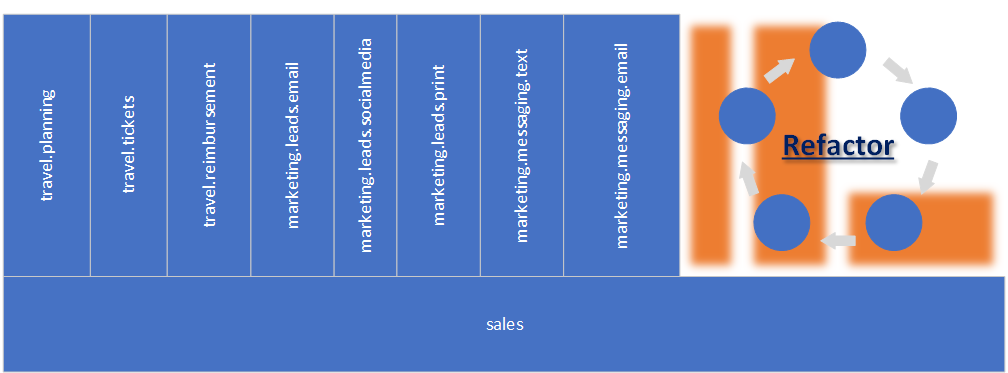

By example above, we can go after immediate sub-components of the marketing component. Common code may also be split and moved into the other components or may have a component of its own, the same way as we did earlier for shared code of the messaging component.

The structure is very flat now, but we have a problem: multiple components that are just shared code. What do we do about it? We need to become more creative now and refactor it!

We need to look closely at the code and try to do the following:

- Find hidden domain concepts within common code and create dedicated components for each.

- Find code that belongs to existing components and can be split and moved appropriately.

- Verify whether the code in fact needs to be shared among multiple components. It might turn out that only a single component uses it, therefore it belongs to it.

- If there is still any code left, then we can create a dedicated utility, common, or shared component(s) for it.

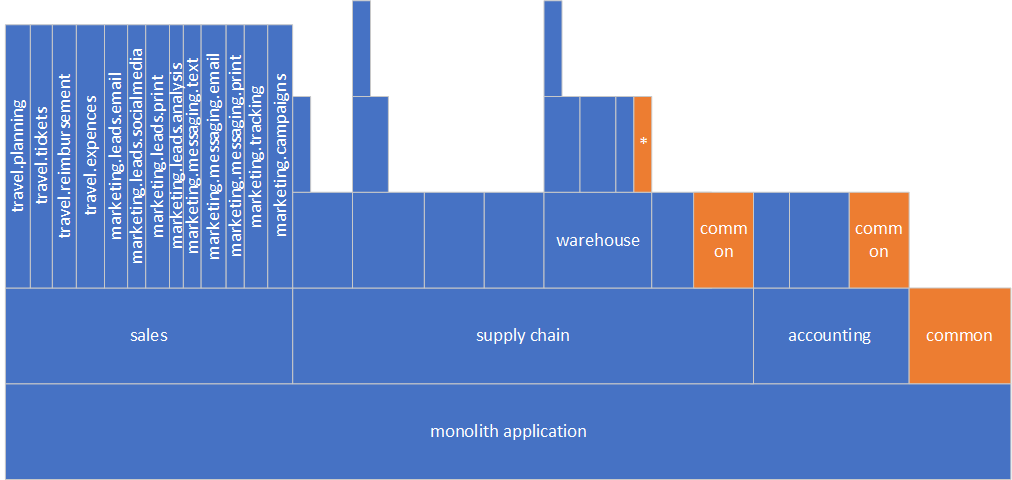

Looking at the big picture, we can see that the sales component has a very flat structure now. But the rest of Monolith is still pretty nested.

We need to continue further and work through the rest of Monolith, flatten, and refactor until we get a very flat structure.

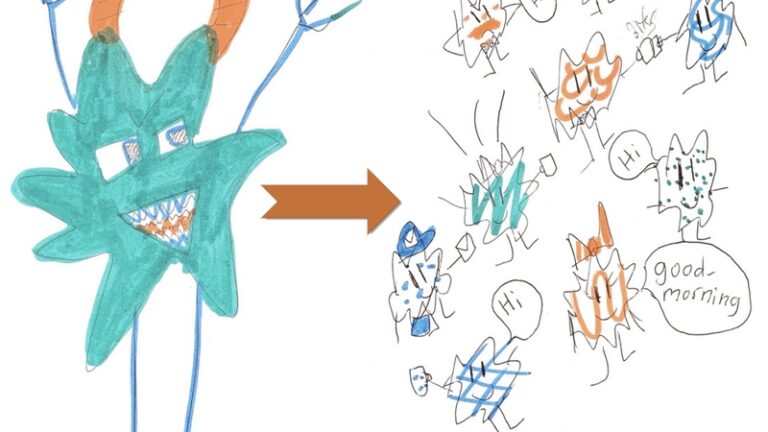

Migrate to Macroservices

Now we are ready to start breaking down the monolith into Macroservices. Macroservices?.. Aren’t we migrating to Microservices? Well, yes, but the first step to microservices is to have services. Leaping from monolith to microservices at once is quite complicated, especially considering that we are working with a live application that is running in production.

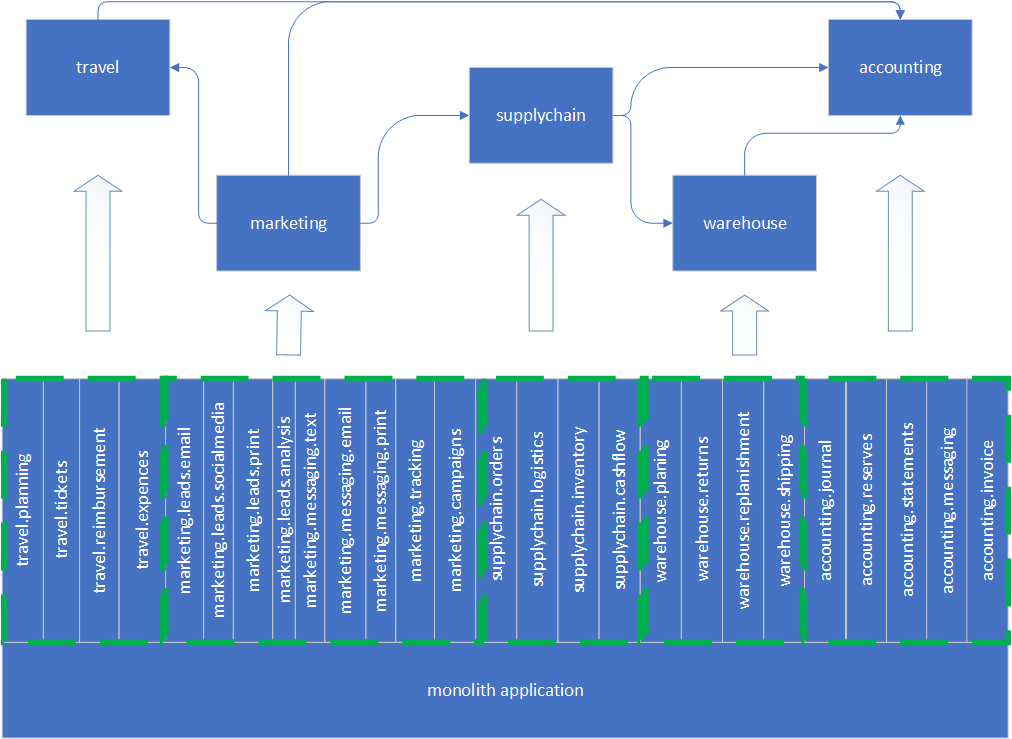

Draw boundaries

Once we have all components flat, we can draw domain boundaries and identify dependencies between domains. In other words, we group components based on their business domain role, then we identify how the groups depend on each other.

The goal now is to have coarse-grained groups. Speaking in DDD terms, a component group may correspond to a sub-domain, bounded context, or even a group of aggregates. If we go with more fine-grained groups, we risk being overwhelmed by the amount of services and exponentially growing dependencies between them. We haven’t done anything yet to prepare team(s) and infrastructure to support a large amount of independently deployed services.

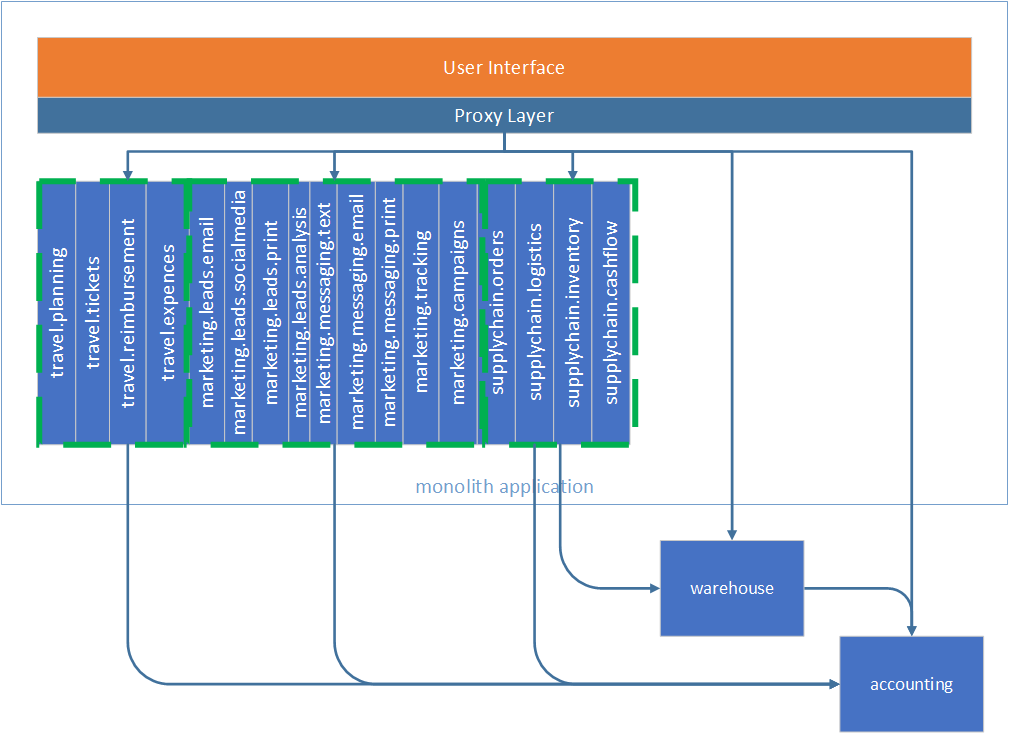

For example, we have five groups of components defined for our monolith: travel, marketing, supply chain, warehouse, and accounting. All groups are cohesive, coarse-grained, and roughly of the same size. We have identified dependencies between all the groups as shown in the picture below. Good news, we do not have cyclical dependencies between component groups; otherwise, we will not be able to migrate gradually, one service at a time.

Hopefully, you can guess what becomes our Macroservices now. And you are right, each group of components we identified becomes a separate Macroservice!

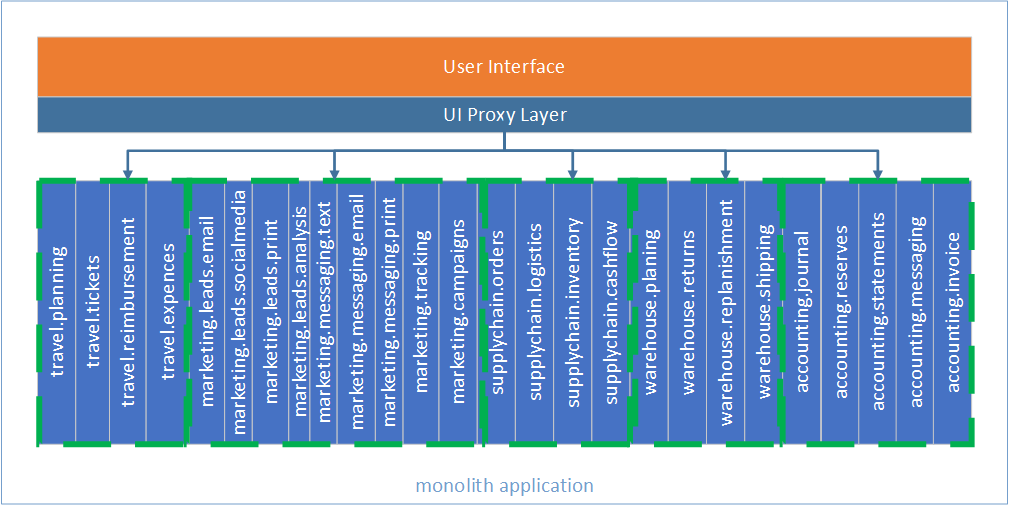

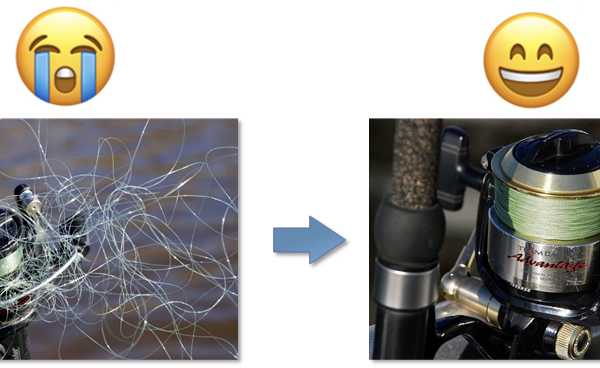

Create remote User Interface

If a monolith has a User Interface that runs on the same machine as the rest of the code and completely relies on that fact, we have a truly monolithic application 🙂. However, Microservices assume remote communications; therefore, we need to prepare the User Interface to communicate “over the wires”. We can achieve that by creating a Proxy layer between the UI and the rest of the application. The The Proxy layer helps to gradually transition our UI to use services, keeping the application live at all times. Gradual transition mitigates large risks that come with “big-bang” releases. Remember to deploy often; do not wait until the whole monolith is fully migrated to services. If anything goes wrong, it is much easier to revert and fix a small piece rather than the entire system.

- Create a Proxy layer that directly communicates with in-process domain code.

- When factoring out services, the proxy can be gradually switching to use services instead of in-process code.

Proxy layer runs in the same process as UI and is responsible for communicating with the services.

Gradually Migrate to Macroservices

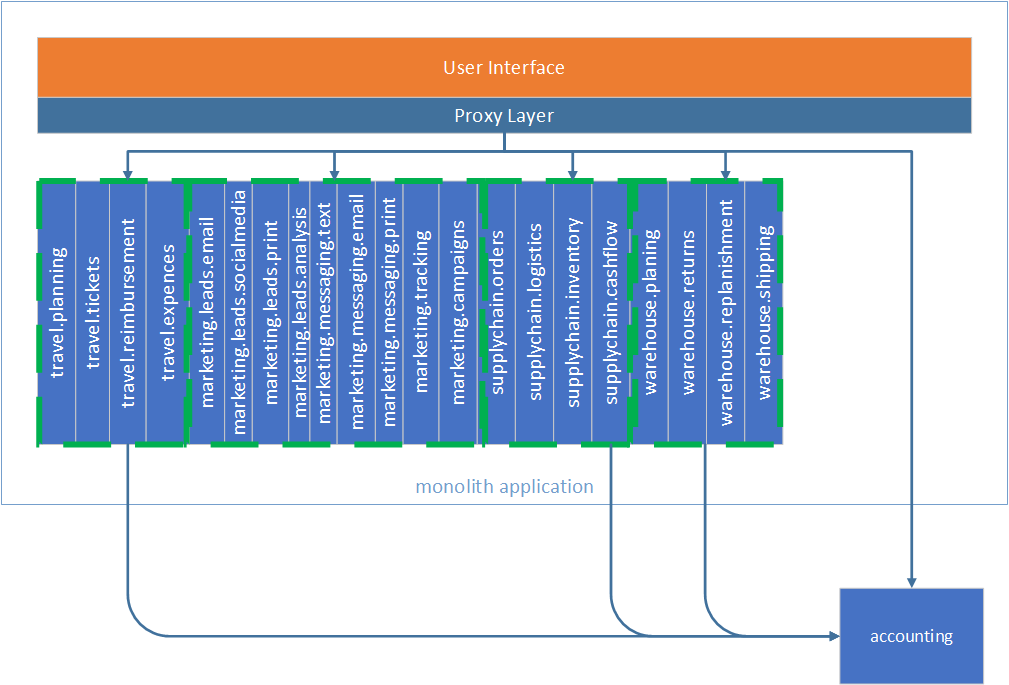

Once we have UI Proxy, we can start decomposing the Monolith. First, we can select a component group that does not have any outbound dependencies. In our case, it is accounting. The proxy now redirects all calls to the accounting service. Other component groups that depend on accounting also redirect their calls to the service.

Next component group to decompose is the warehouse. It does not have any outbound dependencies on the rest of the monolith. It only depends on the accounting service; this is exactly what we are looking for. Building dependencies from a service back to the monolith is a very undesirable thing to do.

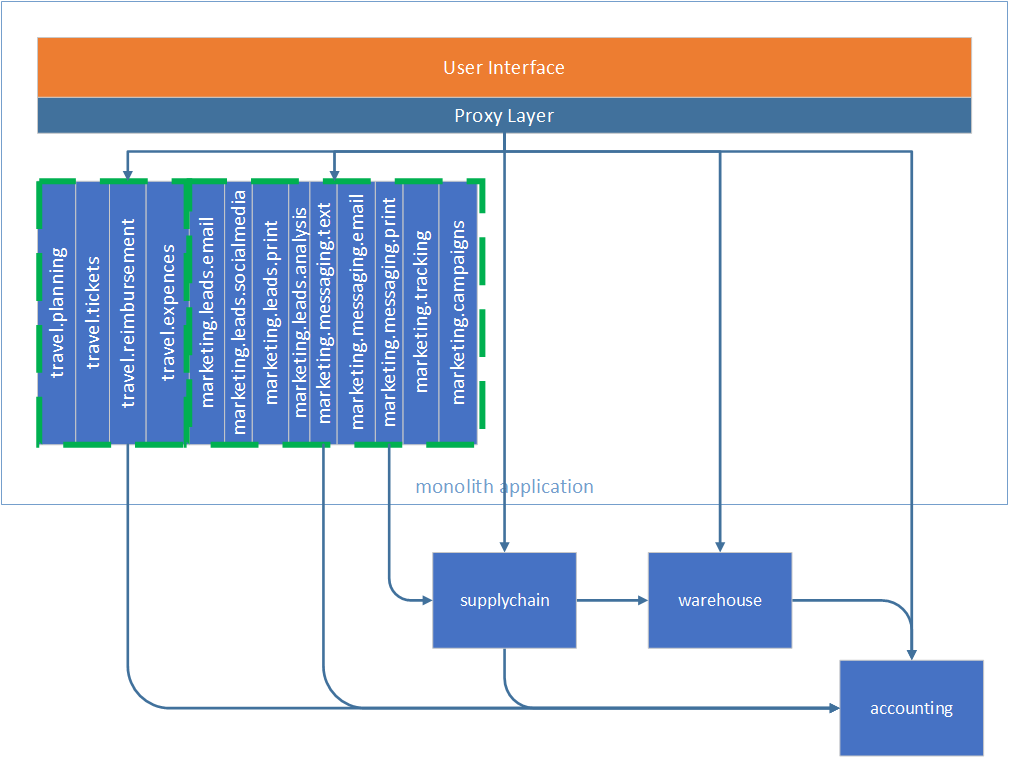

Next is the supplychain component group. It does not have any dependencies on the monolith, so we can migrate it to a service. This is where we are now.

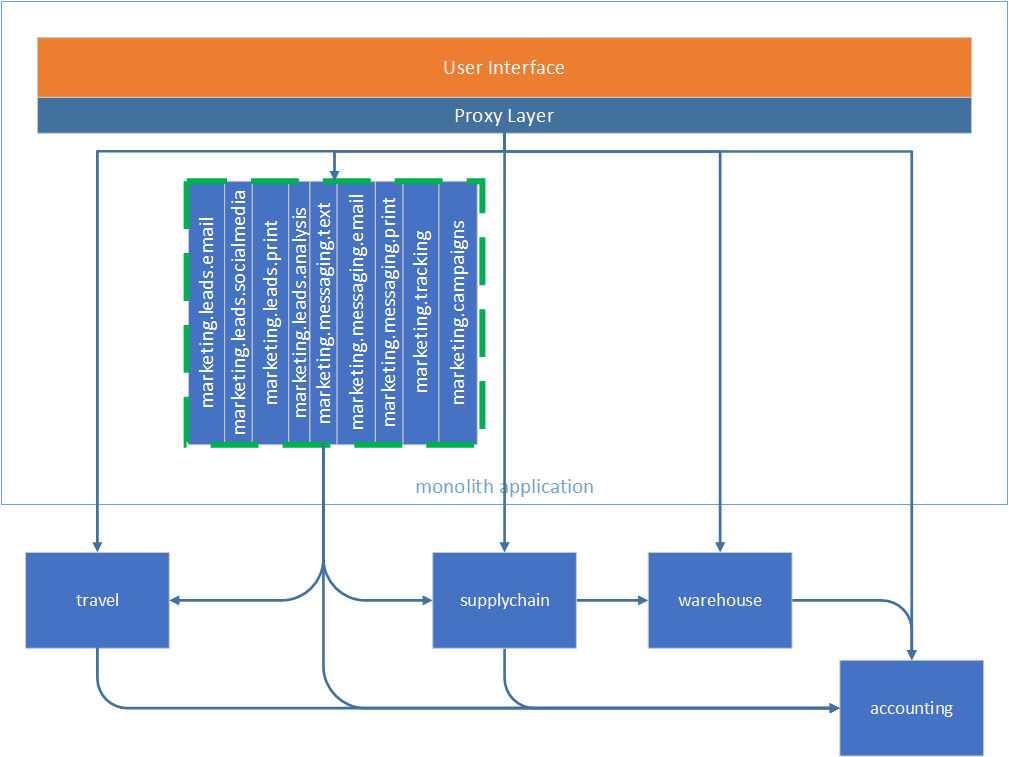

Moving along and migrating the travel component group into a service.

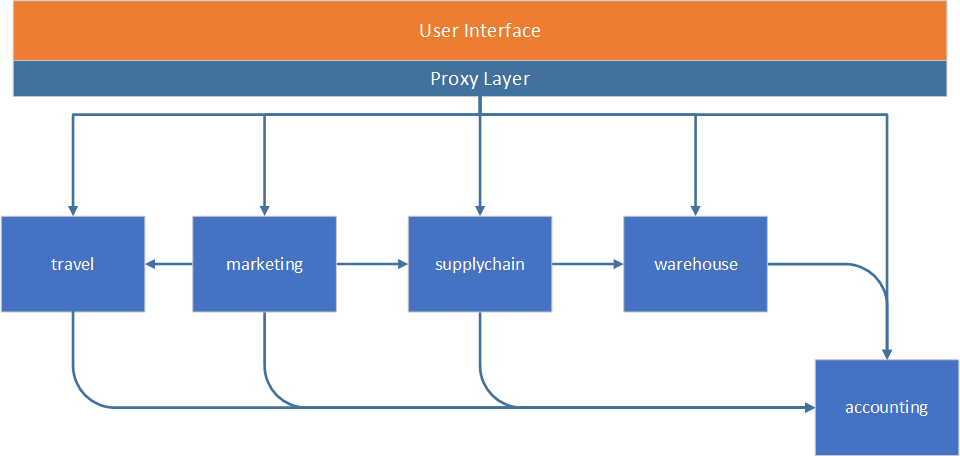

We don’t have much of a code left in the monolith, so let’s go ahead and take the last marketing service out.

At this moment, we decomposed the monolith into microservices. We can look at our new service-based architecture and begin thinking about migrating to Microservices.

Summary

First, we looked at our Monolithic application and made a conscious decision that we need to migrate to Microbreweries. We did consider the pros and cons and evaluated the risks. Next, we refactored and grouped the code into logical components to make migration possible. We identified cohesive component groups and mapped dependencies between them. Then we gradually migrated the Monolith to Macroservices, one service at a time. Now we are going to take it further and migrate a service-based architecture to Microservices, but that is the whole new post.

Further Reading

| Monolith to Microservices: Evolutionary Patterns to Transform Your Monolith, by Sam Newman. |

| Microservices Patterns: With examples in Java, by Chris Richardson. |

One thought on “Migrating Monolith to Microservice Architecture – the Path”