Previous part talked about why using Stored Procedures for writing business logic may be a bad idea. In this part, we continue on this subject but are going to look at the problem from an architecture angle.

Table of Contents

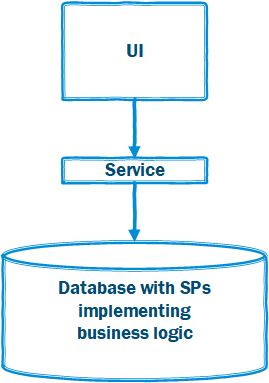

Typical Stored Procedures based application

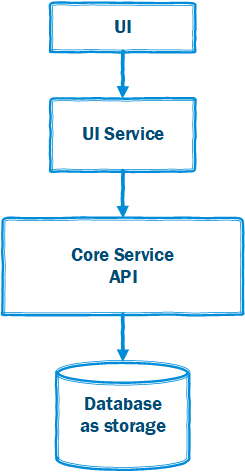

Typical application which heavily uses SPs for business logic may look like this.

Most of the business logic is implemented by SPs; therefore, the database takes most of the responsibilities. Sometimes, applications like this also have heavy UI, which takes a lot of responsibilities too and may duplicate business logic implemented in SPs. The service layer can be very thin and serve as a connector between the UI and the database. In this case, it plays the role of a path layer. However, if the UI layer is capable of connecting to the database directly, then the service layer may not even exist. So, a three-tier application becomes a two-tier application.

What is wrong with a design like that?

How to integrate

Applications typically do not live in isolation. They need to talk to each other in order to perform tasks. For example, an eCommerce website may have an orders system that talks to a warehouse system to check inventory and a tax system to calculate sales tax for an order.

If we have all business logic written in SPs, we have several options to make systems talk to each other.

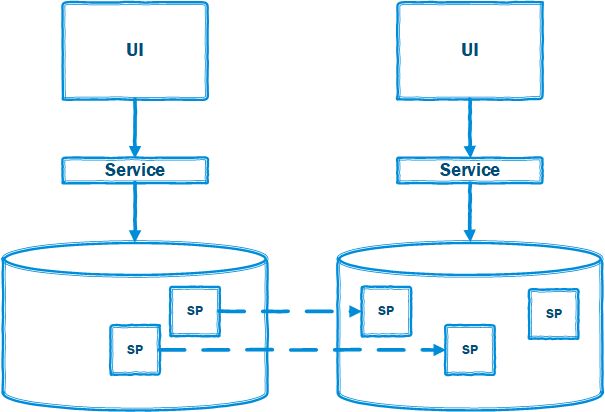

Database to Database

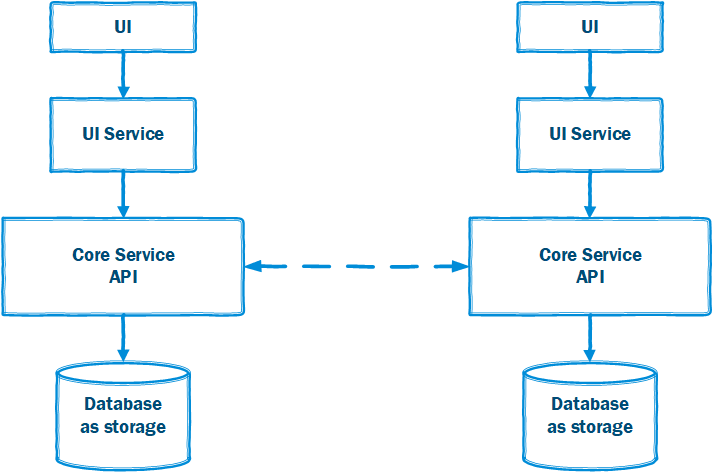

Multiple RDBMS support a notion of schema. Schema can be thought of as a namespace within a database or a way of grouping related database objects. Database-to-database approach is shown below, where one database integrates directly with the other database.

In such a case, applications can access each other’s databases (or schemas) directly by calling SPs. This approach has several significant problems:

- Coupling on the database level. In case one application needs to have a change in a Stored Procedure interface, the other application’s database may need to be changed as well. Because the database is the lowest level, the change may ripple through both systems, which is very costly and tedious.

- The dependencies between different databases or schemas may not be so obvious to see unless there are tools to help with identifying dependencies.

- Exposure of Database tables. If permissions are not set up carefully, then one application may start directly accessing other applications’ tables. It is very tempting and easy to take a shortcut and just join a table from another database or schema, even though it doesn’t belong to the application. And now we have even more tightly coupled applications.

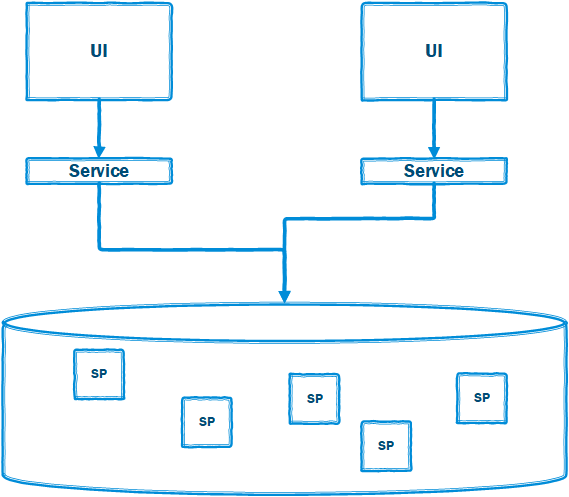

Shared Database

This design inherits all the disadvantages of database-to-database integration and adds more to it due to the lack of clear boundaries between applications.

Shared database design may happen in a monolith application or poorly designed microservice architectures. With no boundaries between applications, even a simple change in any part may cause changes in other parts or, if not careful, even break other applications. This increases the cost of changes and maintenance dramatically.

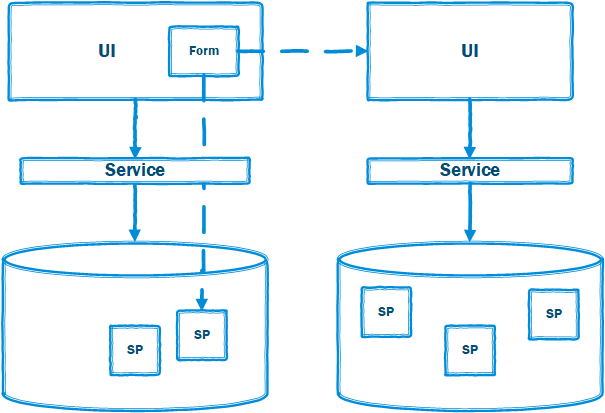

UI to UI

UI to UI integration is also possible by sharing libraries, packages, or components between applications. While sharing libraries and packages with basic UI building blocks (buttons, drop-downs, menu items, etc.) brings certain advantages if used wisely. For example, styles and basic component designs can be shared among a variety of applications, creating a unified appearance for the entire system.

However, integrating an UI layer while having business logic implemented in stored procedures has its own problems.

Imagine we have two applications which share a UI form. The form has 2 variations: one application needs 7 fields in the form, but another application needs only 5. We have implemented all business logic behind the form in a few stored procedures. What issues can we encounter down the road?

- The 7 vs 5 fields variation makes its footprint in every layer of the shared form (UI, Service, and Database) because all business logic (validation, persistence, etc.) resides in SPs. A stored procedure which saves the form field may need to have 7 parameters (one per field), where 2 will be optional to accommodate the 5 fields scenario. The same is true for the service layer.

- Increased complexity in all layers with more variations. What if we need to add another variation of the same form with 8 fields? Now the service layer and the SPs need to be changed to have 8 parameters instead of 7.

- More duplicated code. What if we decide to split and have two forms with 7 and 5 fields instead of adding new variations? Because business logic resides in stored procedures, we will have to have 2 service layer endpoints and 2 SPs, one for each form.

How to scale

Having most of the business logic implemented in Stored Procedures limits options to scale. Unless the RDBMS supports horizontal scaling, we would not be able to increase performance and robustness by scaling horizontally (multiplying instances of the running database). The only option we would have is to scale vertically or increase the “size” of the machine where the database runs, e.g. add more memory, faster CPU(s), faster disk. However, with this method, we will have a limit on how far we can go. The larger the machine, the more expensive it becomes, and the cost rises faster than the size.

How to make it right

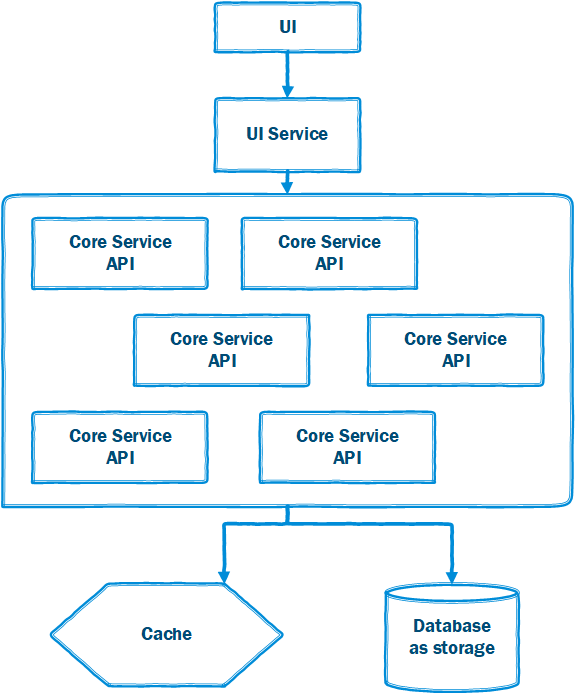

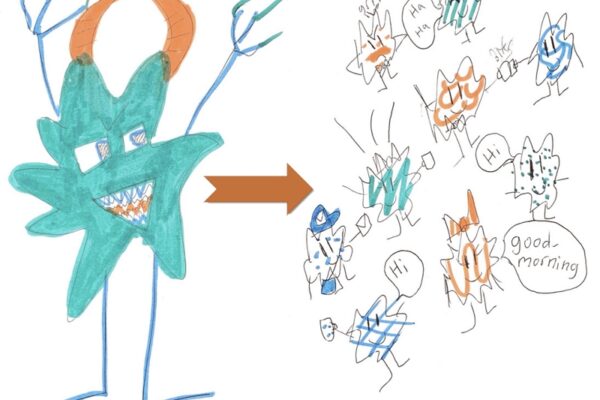

Let’s try to improve our design and stop writing SPs with business logic. Let’s move all business logic from database SPs to the service layer. Here is how our application looks now.

The changes are pretty significant.

- Now we have Core service. It is an integration point for our application. It implements APIs other applications can integrate with. Core service implements all business logic required. The interface of Core service can be fine-grained, allowing more granular interactions with our system.

- We have UI Service. The API is course-grained with a primary focus to serve User Interface. Our Core service’s fine-grained API might not be perfect for our UI, because in some cases we may need to make multiple calls to the Core service for a single UI action. For example, we have a UI dashboard which needs multiple collections of data. To load all data for the dashboard, we can implement a single request in the UI service which will aggregate data from multiple sources, including the Core service, and return it as a single response.

- We have a database as storage. Yes, we think of the database as storage only. Its primary responsibilities are to store data, ensure data integrity (using constraints), and perform operations with data. No more business logic in the database. Stored Procedures.

- We have UI which can be anything (Web, Mobile, or Desktop). The responsibility of UI is obviously to interact with the user. UI can also implement simple validation of data entry (e.g. non-blank form fields, formats of emails or phone numbers) and may include a minimum of business logic if it’s absolutely needed.

It is fair to say that Core service and UI service can be merged if User Interface can handle fine-grained API of Core service and does not need any “back-end” help.

How to integrate

Integration with other systems is a breeze as we have a dedicated Core service for that. We can use other applications’ API services so that other applications can use our Core service.

How to scale

Scaling is also a piece of cake. It’s built into our design. If we need to increase the performance of our system, we can.

- Add more instances of Core and UI services. If we followed the Twelve-Factor App recommendations or just have stateless services, then horizontal scaling is our friend.

- If the database becomes a bottleneck of our application, we can add a layer of caching with Redis or other caching technology.

- If we have a Web UI, then some of the static content can be delivered through a CDN.

Summary

Summary can be as short as “Do not wring business logic into Stored Procedures”. Having business logic in SPs may work for some time, but it will likely limit your options in the future when you need to integrate with other applications or scale your application horizontally. Scaling a relational database is not as easy as scaling a stateless service. Integrating applications at the database level can lead to chaos and code that is difficult to work with.

As always, alternative opinions are welcome!

One thought on “Why Not to write SQL Stored Procedures – Part 2”